Wine bottle closures

It’s easy to overlook, but the small piece that seals a wine bottle determines how the wine ages, tastes, travels, and is perceived. Wine bottle closures today range from traditional natural cork to screw caps, synthetics, agglomerates, technical corks, glass stoppers, and crown caps, each with trade-offs in oxygen management, TCA and taint risk, sustainability, and of course the cost.

Many estates mix and match: natural cork for age-worthy reds, screw caps or technical corks for aromatic whites or wines meant for early drinking, and crown caps for sparkling.

Wine bottle closures have seen a gradual evolution over centuries from simple plugs to high-tech seals, essential for the aging and preservation of the wine and its quality.

This article explores that evolution, history of tests by famous producers, various closure types, the research and development of closures, the pros and cons, usage statistics, and future trends.

Let's take a closer look now ...

History

History of wine bottle closures begins in antiquity when cork was first used to seal Greek and Roman amphorae, popular for its ease of usage and production and seal-tight qualities. However, that wasn't always enough: the cork stopper would sometimes be sealed with an additional layer of amongst others clay to ensure a complete seal.

Cork’s earliest dominance waned with wooden barrels taking over storage and shifting wine commerce. But it wasn’t until glass bottles became widespread and uniform in the 1600s that cork made its major comeback. Dom Pierre Pérignon, the French monk who is especially known for the Champagne’s rise and nowadays is a champagne brand by itself, pioneered shaping cork into cones to withstand sparkling wine pressure in the late 1600s to early 1700s. Cork combined with wire cages and foils became then the standard for sealing bottles for centuries after.

Despite attempts at alternatives in the 19th and early 20th centuries, cork held fast for quality wines.

Wine closures research by famous wine domains

In the second half of the 20th century serious tests were done by leading wineries to challenge cork’s limitations, leakage and cork taint (caused by TCA).

Penfolds (Australia) started in 1957, putting Stelvin screw caps on their top Grange Hermitage red; they hid them under foil at first because customers thought screw caps meant cheap wine, but tests showed the wine aged smooth for 20 years without taint. In New Zealand, Cloudy Bay switched Sauvignon Blanc to screw caps in the 1990s after side-by-side tastings proved the crisp fruit stayed longer and no cork or any other flaw or lesser quality was detected.

Rioja heavyweights like Marqués de Riscal and Ribera Del Duero topproducers like Vega Sicilia tested caps on premium Tempranillo in the 1970s, storing bottles for 10+ years and finding reds developed just fine, though they kept using cork for tradition.

In Bordeaux Château Margaux undertook 20-year blind tastings comparing closures, affirming cork’s superiority for long-aging reds but acknowledging screw caps work well for whites. Ridge Vineyards in California still tests 12 closure types yearly on Zinfandel and Cabernet, to determine how each closure ages the wine and performs ongoing trials including Diam-like options.

Bottle Closure Types

There are number of wine bottle closure types, below the most used:

-

Natural cork: Single piece cut from cork oak bark, offers micro-oxygenation ideal for long-term aging.

- Colmated cork: Natural cork with pores filled for smoother extraction and better seal.

- Agglomerated cork: Granules bonded together, cost-effective for wines consumed early.

- Technical cork: Agglomerate with natural disks at ends, balancing cost and aging potential.

- Diam cork: Treated technical cork. Granules are purified via CO2 process for no TCA, custom permeability. Ideal for still wines needing consistency without losing cork's elasticity.

- Synthetic corks: Plastic-based, consistent with zero TCA risk, used for short-term wines.

- Screw caps: Aluminum with specialized liners controlling oxygen ingress, prevalent for whites and early-drinking wines.

- Glass stoppers: Resealable glass with inert seals, gaining popularity for premium presentation.

- Crown caps: Used for sparkling wine secondary fermentation, replaced by cork with wire hood for bottling.

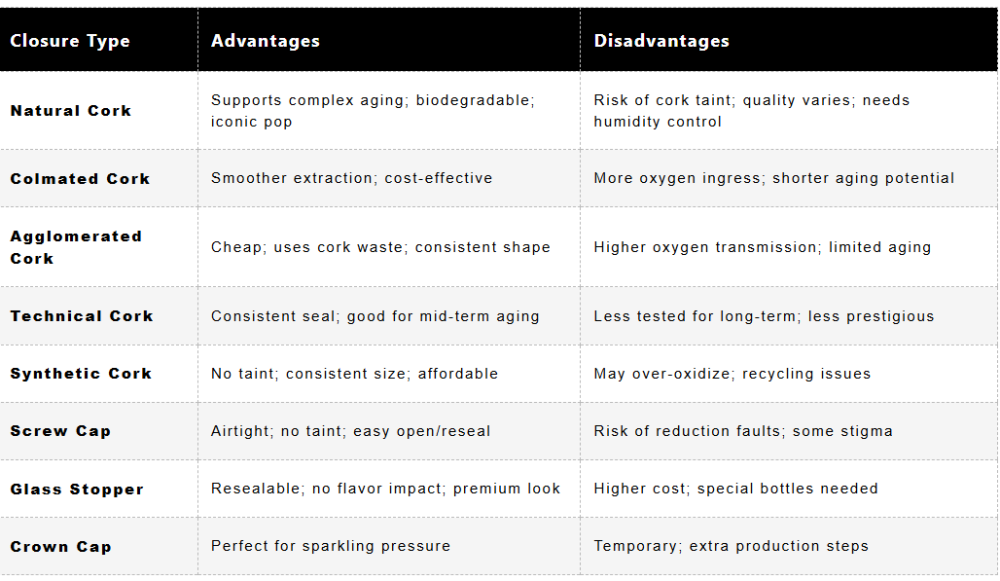

Each type of closure has its typical pros and cons and best practice of usage.

Advantages and Disadvantages of Different Wine Bottle Closures

Research and Development

Research and development on closures for wine bottles is oriented to oxygen transmission rates (OTR), which is of course critical for wine aging and the final wine quality. Cork producers use steam and/or CO2 treatments to reduce TCA as much as possible. Renowned labs like UC Davis and the Australian Wine Research Institute Scientific perform their research intensively, like decades-long bottle aging to objectively test closure performance.

Screw cap liners have changed and increased in quality using multi layer material which resembles the slow oxygen flow of a cork.

Bio-based synthetics are increasingly reducing the plastic eco footprints. And new experimental closures are tested by monitoring the bottle conditions in real-time.

Sustainability is an import topic for R&D, with cork remaining a carbon storage and producers promote recyclable or even biodegradable solutions.

Are quality corks getting more rare and more expensive?

No, there is no evidence that rising wine consumption is causing cork quality to go down. The cork industry, led by Portugal (supplying around 50% of all corks), harvests bark from cork producing oak trees every 9 years without felling them. A single tree produces material for 100,000+ corks over 200 years.

Research from the Cork Quality Council and ETS Labs shows that TCA taint rates stabilise at around 3% or below through steam/CO2 treatments and "releasable TCA" testing. That number dropped down significantly from higher levels 20 years ago, despite around 16-40 billion bottles sealed yearly. Issues like yellow stain (linked to chlorophenols/TCA via microbiota) keep appearing in low-grade cork but are managed via genomic studies identifying precursors for prevention.

High quality natural corks for high-end and expensive wines aren't increasing in price due to shortages either. Demand for fine wines (where cork is used in 90%+ of the bottles) is met by quality controls ensuring consistency; processing is the cost factor (e.g., ultra-clean slabs for 20+ year aging), not supply limits.

Studies from amongst others CRAG and APCOR confirm that ongoing R&D keeps high-grade cork viable without prices increasing. And prices stay stable while alternatives like screw caps are increasing in usage in white wine bottles.

Economic losses from taint (around $1-10B/year historically) are factor that makes innovation increase, not scarcity.

Statistics on Usage

Cork is used in about 70% of the world's 40 billion wine bottles yearly, jumping to 90%+ for premiums over $20. Portugal supplies 16 billion corks from its oak groves.

Screw caps claim 50% in Australia and New Zealand, 25% in Europe, mostly used in white and rosé bottles.

Technical/colmated corks represent around 20-25%, while synthetic corks hold under 5%.

Sparkling wines universally start with crown caps before the final cork and cage.

The usage of Diam closured is growing fast, from a niche closure to rivaling the natural cork, especially is US white wines.

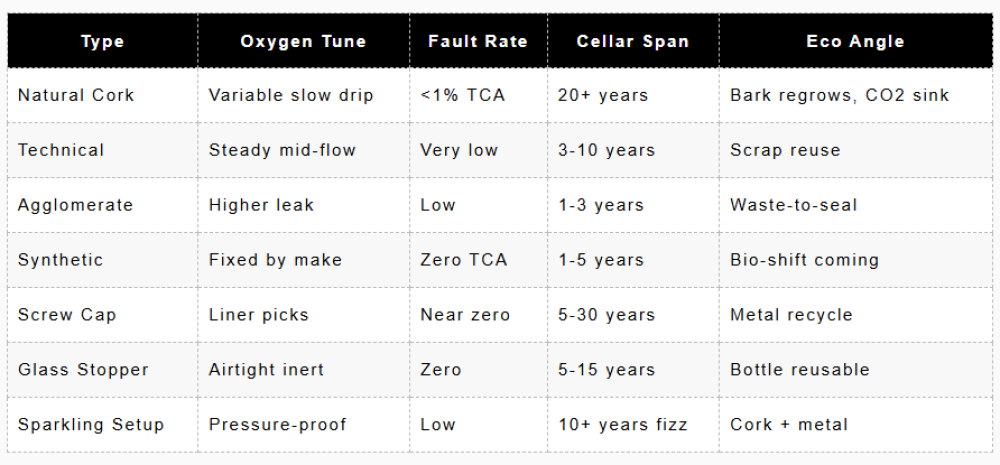

Wine Closures Comparison Overview

Future Developments

It is expected that TCA reduction will go on through enhanced (AI) detection and treatment technologies, keeping natural cork vital for premium markets.

Diam closures may lead the development in so called "clean cork" with versions like Origine for mid-to-long aging as 20-year trials grow fast.

Screw cap liners will offer even more oxygen control, so being more and more a competitor to the corks benefits.

Sustainability will further drive the market, toward recyclable materials, bio-based synthetics, and cork forest expansions to lower climate change consequences. Glass and magnetic closures could rise for niche markets for reseal and reusability.

Market forecasts indicate non-cork closures could reach 40% of global still wine closures by 2035, mainly for sub-$15 wines, while natural cork retains prestige for fine wines.

Blockchain and digital traceability will increase the consumer's trust in provenance and quality.

Three Fun Facts

There are many fun facts and funny stories about wine and wine closures. We aleady mentioned a few in this article, here are three more:

- A single cork oak tree can produce enough bark for over 100,000 wine stoppers during its 200-year lifespan, and the tree just keeps growing back the bark every 9 years.

- Screw caps were actually invented in the 1950s but winemakers hid them under fake foil wrappers for decades because people thought "no pop, no party": one Aussie winery even got hate mail for removing corks on fancy reds.

- In the 1800s, some rich folks sealed bottles with custom glass "blobs" stamped with their family seal instead of corks—it was like putting a wax stamp on a letter, but for booze, to prove it hadn't been tampered with.

What closure for what purpose ...

Wine closures are very versatile and are used in very different ways. However, some guidelines can be defined:

- Big reds for 10+ years: Natural or top technical cork.

- Zippy whites and rosés: Screw cap with medium liner.

- Quick-party bottles: Agglomerate or synthetic.

- Bubbly builders: Crown closures.

- Restaurant by-the-glass: Glass stopper, reseal magic.